UXOs are UCPs

(Unexpected constraints to production), and other lessons from life in Lao PDR

I have been a field pathologist for… well, let‘s just say over 15 years. I have been fortunate to travel to some exotic locations for my work such as: New Zealand, Spain, China, the Philippines and North Queensland. I have seen some usual and not so usual constraints to production – cold, heat, gradient of land, inter-rows so waterlogged the tadpoles nearly have legs – but nothing prepared me for one of the major constraints to production in Lao PDR, the unexploded ordinances (UXOs for short).

I was in southern Laos in February and March this year to work with colleagues from the Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Organisation (PAFO) to survey for banana leaf diseases and do some training. Prior to my trip I had done my research; I knew that Lao PDR was one of the most bombed countries per capita from bombing undertaken 1964-1974 in the course of the second Indochina (Vietnam) war. I knew that around a third of the ordinances dropped had not exploded and could still pose a risk – but knowing is different to coming face-to-face with a little torpedo shaped metal object in a tree next to a banana plantation one is surveying.

Walking into the paddock intended for survey, Mr H, the farmer, pointed to the crook of a tree and motioned for my PAFO colleague Ms Seng to look, she did and turned with eyes as big as saucers and speechless. Of course I had to look – same effect. Of course Professor Lester had to have a look too – his eyes as big as saucers and he said a naughty word. And then, as if nothing happened, we carried on towards the banana plantation – I decided I would walk on the compacted sides of the paddock and not cut diagonally across the freshly ploughed field next to the banana plantation.

Image 1. The “bomb” in the tree later identified as a 60mm mortar round probably a M69 Training/Practice Cartridge.

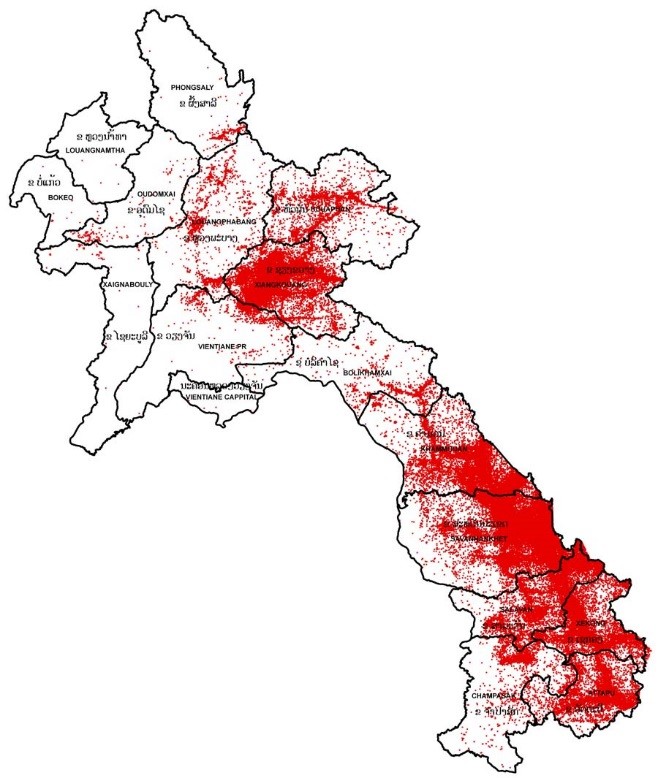

At lunch after that little episode it was time to do a bit of Googling – I’d had a vague idea that the UXOs were mainly in the north – I was so wrong – unexploded ordinances litter the country-side in Lao PDR even nearly 45 years after the end of the of hostilities. So how does this impact on production? Any time the ground is disturbed – such as the grading of a rice paddy, the hand repair of the walls of the rice paddies or the clearing of land to plant crops – there is a chance that the UXOs can be disturbed and go off – injuring or killing farmers. There are clearance teams going out every day, brave men and women who painstakingly check for UXOs and then remove them, slowly clearing the land so that agricultural development can take place. A lesson for anyone considering working with soils or digging in Lao PDR – dial (a UXO clearance team) before you dig. An important thing to note though is they generally only clear the top 25cm of soil, keep that in mind if you have more extensive work in mind.

Image 2. Map of Lao PDR, red indicates the number and location of bombing runs according to US bombing records (source: http://www.nra.gov.la/uxoproblem.html ). For more information on one organisation helping people move on from effects of UXOs visit http://copelaos.org/ .

Enough of the drama Jay – what about the bananas? The aim of my 6-week placement was to catalogue which banana leaf diseases are present in Southern Laos and provide training on recognising the diseases and how to culture the fungi which cause them. In six weeks we visited 25 small holder plantations in 4 provinces in Southern Laos and collected 41 samples from 7 different banana varieties. The major disease problem we saw was banana freckle but generally the plants were relatively free of leaf diseases. The major constraint to the current production system was banana borers which tunnel into the stems of the banana plant and cause a wilt and a decrease in yield.

Image 3. Banana borer exit holes on stem of banana plant. The borers tunnel through the plant, cause a wilt and decrease the yield of the plant.

Image 4. Typical small holder banana farm with wide row spacing, minimal de-leafing for leaf disease control and very few inputs of fertiliser, fungicides or herbicides. Mr H enjoys banana farming because he has time for other work and time with his family. He learnt banana farming techniques from his family.

The majority of plantations we visited we about ½ to 1 hectare of local favourite variety ‘Kuoy Nam’. The production systems are relatively low input but growers can make good money from selling their bananas and have time to spend with on other jobs or with their families which is important in Lao culture. The plantations we visited were some of the lowest input banana systems I have seen, very wide spacing between plants, no additional fertilisers, very little de-leafing, very little to non-existent weed and sucker control. But hand on heart I cannot suggest changes to the system except for a few cultural control methods to control the borers – why wouldn’t I suggest the growers grow higher yielding varieties? Or use fertilisers or irrigation? Why wouldn’t I want more money in the pockets of growers?

It is a case of risk verses reward. Let me explain: one visit to Mrs P’s farm is etched in my mind. In the dry season Mrs P hand-digs holes into her rice paddies, plants watermelons and then carefully hand waters them until the fruit are big enough to sell as an important cash crop. Normally in February there would be melons plants covering the paddies with fruit ready for harvest. When we arrived in this February the plants were small, with small, misshapen fruit, some of the plants were dead. An unknown virus had wiped the plants out – once the plants started showing symptoms of virus and infestation with a range of potential insect vectors Mrs P had bought one insecticide, it didn’t work, so she bought another and another…. to no avail. She told me she had spent 5 million kip trying to control the virus(es). That is about $800 – in a country where the average monthly salary is about $350 and one would expect farmers are not earning anywhere near the average. This experience made me carefully consider the context in which I give advice – it was a lesson for me – should we aim for growers to have the highest production possible? Or do we work with them to have the most suitable production for their lifestyle and capital situation?

Image 5. Dr Madaline and Ms Seng discussing with growers practices they may be able to implement to help control watermelon viruses.

I feel like I have told a story of doom and gloom – but my time in Lao PDR was far from that. We had a successful survey. Information on the status of banana diseases have been shared with our Lao colleagues in various departments and we have established a network for the sharing the results of samples which we are still processing. We have a number of WhatsApp groups for sharing of images and information.

Image 6. Some of the lovely people I met on my assignment. Three families work together to run this vegetable farm, they use raised beds, crop rotation and rice hull burning to manage plant diseases.

Personally it was very rewarding. I learnt so much from my Crawford Fund mentor Professor Lester Burgess and from my PAFO colleague Ms Sengphet Phanthavong. As a Plant Pathologist I had incredible professional development opportunities seeing pest and disease issues I would not see in Australia. I got to do banana survey via boat! We surveyed the bananas on some of the islands in the 4,000 Islands on the Mekong – what an amazing experience!

Image 7. Disease survey via boat was novel for me but also worthwhile. Ms Seng, myself and Prof Lester (left to right) were able to inspect local banana plantations and also see the vegetable gardens on the islands of the 4,000 Islands group in southern Laos.

Lao PDR has always fascinated me and I feel very privileged to have spent some time there. The people were so welcoming – my colleagues at PAFO, the small holder farmers we talked to, other international volunteers and the people in the shops and hotels. I adopted the traditional Lao skirt, a sinh, and had such a positive response from people – it made my day when an elderly lady sitting on her verandah gave me a big smile, a wave and gestured to my sinh as I walked past on my way to lunch one day. I look forward to the day when I return and I can learn more about this complicated, beautiful country.

Dr Jay Anderson is an Associate Lecturer at The Univeristy of Queensland. She conducted her research as a Plant Pathologist (Tropical Fruits) through the Australian Volunteers Program and the Crawford Fund. If you are interested in undertaking a volunteer placement overseas, please reach out to the Crawford Fund via their website. They welcome expressions of interests and you can read more about their Next Gen opportunities here.