Jumping puddles in paddy fields

From the dusty van window I looked out at the passing countryside. I was hypnotized by the blur of verdant green paddies, monolithic water buffalo grazing contently, and village children balancing on rickety bicycles. I braced myself as we thumped into another pothole. The traditional Lao music wafting from the stereo did not miss a beat. I popped another lotus flower seed into my mouth, and smiled inwardly— this was my new home.

Laos is a destination steeped in history, with brooding jungle, jagged limestone cliffs, and ethnic tribes rich in tradition. Agriculture accounts for 80% of the employment in the country. It is no wonder that its people have such a strong affinity to the land, and farming holds key social, cultural and spiritual significance. Until recently, crop and livestock production has been primarily a subsistence activity, with limited local or export trade. Southern Laos is an agricultural economy in transition, and with rising rural poverty and an elevated risk of food insecurity, the Government has identified agricultural and rural development as a national priority.

I have had the privilege of traveling to Laos to live in the city of Savannakhet, and work for the Provincial Agriculture and Forestry Office (PAFO). Here I have been assisting Charles Sturt University researchers and collaborating organisations, both national and international, on developing improved farming and marketing systems in the southern rainfed regions.

Rice has long been the most important food crop in Laos. Archaeological evidence has found that rice has been grown in the region for at least 6,000 years. With an average annual consumption of nearly 170 kg of rice, it is no surprise that the Lao expression “to eat” translates as “to eat rice”.

One of the project focus areas is mechanization for improved crop establishment and management. As part of this focus the use of direct seeding technology is being investigated. The farmers in Savannakhet and Champhone provinces are eager to trial direct seeding as an alternative method of planting rice to the conventional broadcast sowing and transplanting. The direct seeding method is driven by labour savings (eliminating the intensive transplanting process), avoiding root damage during transplanting, and providing easier weeding of uniform rows. Improved rice establishment under direct seeding also increases soil water retention, reducing nitrogen losses due to deep percolation.

Direct seeding places the seed under the soil, as opposed to broadcast on the soil surface. A narrow cutting tine creates a small furrow, in which seed (and sometimes fertiliser) is placed, and a following blade covers soil over the furrow. This technique is particularly important with increasing seasonal variability- with rainfall coming later, seeds buried in the soil have a greater chance of survival. Direct seeding also reduces the risk of establishment failure due to water shortage at the time of transplanting. Labour shortages can also occur during the peak transplanting periods. Direct seeded plants tend to mature 7-10 days earlier than transplanted rice, mainly due to the avoidance of stress that results from being pulled from a nursery plot and needing to regrow fine rootlets.

Rice can also be planted with a drum seeder in level, wet land. Pulled along manually, the drum seeder is a fast planting technique. However, uneven seeding may occur with a drum seeder, subject to operator consistency, and transplanting may be required where too many seeds are deposited.

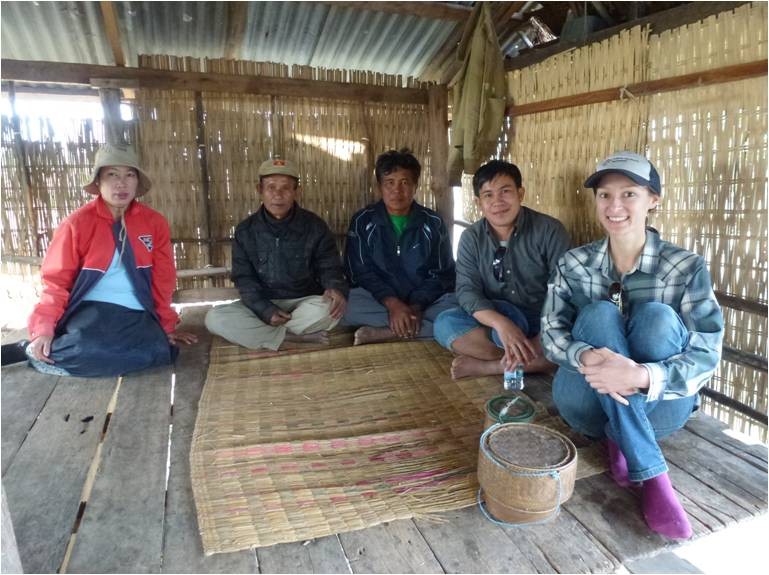

The Lao have a saying— “never eat alone, because your food will not taste delicious” — which I contemplated as I sat cross legged on a woven straw mat, and rolled a ball of sticky rice, dipped it in a chili paste and washed it down with fresh coconut milk. The dozen Lao farmers eating alongside of me delighted in my facial expressions and pushed another plate of freshly harvested greens closer to me. It never ceases to amaze me the variety of fruits and vegetables that they grow in their modest gardens, and the flavors they are able to create.

Improving crop production is important for national food security, for increased commercialization, and climate-risk aversion. Direct seeding technology in the southern rainfed regions of Laos offers a notable opportunity to improve rice production systems.

As a researcher in international agricultural development, I am thoroughly excited about the future and to be part of this dynamic and rewarding industry.