The power of Language “To Pasa Lao, or not to Pasa Lao, that is the question”

English is the predominant language of science. For me it’s my first language but for many of my colleagues it is their second or third language. So, I ask myself, when working overseas, is it best to speak local or to speak English?

When I volunteered in Laos, I was determined to learn the language so I could chat with my friends and colleagues, with tuk tuk drivers, watermelon farmers and, when needed, shout at the stray dogs in a language they understand.

However, the more I’ve worked with people in places like Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam, I’ve realised that speaking English isn’t always inconsiderate.

Me speaking English means that my colleagues can practice their English skills, which can help them to communicate with foreign scientists at international conferences, write technical reports and potentially enable them to study and work at international institutes.

Find the balance between local and English

Many words that we use in science do not exist in Lao language, so to develop an understanding of a word or a concept it needs to be relatable, and the easiest way to do this is through hands on learning.

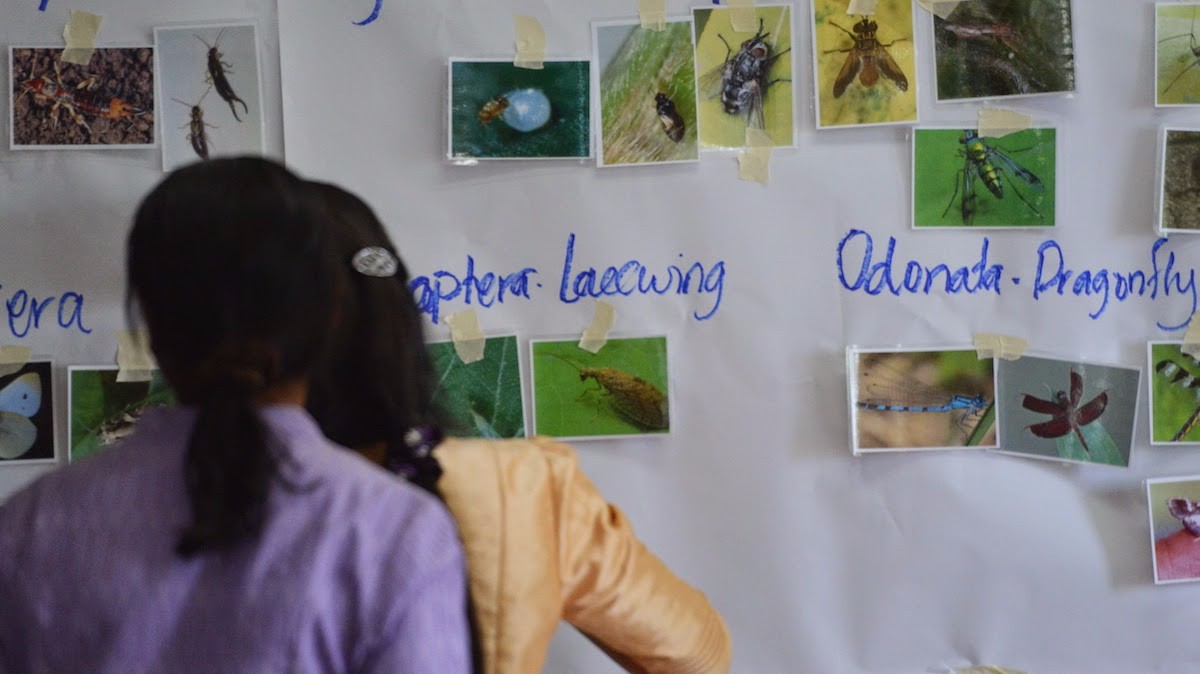

When we conduct insect pest management training workshops with people who don’t have a great understanding of English, we’ll always work with one of our colleagues who can help translate. We also use flashcards and insect specimens as visual ques, conduct insect field walks to collect specimens, all the time introducing a little English as you go.

Picture 1: Flashcards and flip charts, a good tool to manoeuvre around the language barrier

The key is to tailor the language to the audience.

For instance, when running a farmer field day, present in the local language. If it is a mix of industry representatives, local and foreigner collaborators and government officials it might be easier to present in English, with dual local language/ English notes provided. When developing protocols for a monitoring program, it might be more valuable for all notes and instructions to be presented in the local language.

What it comes down to in the end is the audience. Who are you working with and what do you want to convey? Non-English speakers are not going to benefit from technical advice in English, the same as an entomologist doesn’t benefit from technical medical speak, its foreign.

Picture 2: Hot tip: Find a fluent lao-English speaker to give you a hand (Ms Kaisone Sengsoulichan)

A few points on writing & publishing in science

A few years ago, Lindsey Bell wrote a RAID piece on publishing in research for development, and he speaks about mentoring and coaching your collaborators in publications. One of the suggestions for this is workshopping, breaking down the task so that it is easy to work through and manage. This is such a valuable training exercise in supporting your coleagues in developing English writing skills, and one that cen be applied in many areas of agricultural research.

So, when working overseas speak English. Sit down and have formal or informal lessons with your colleagues, they want to practices reading, writing and spoken English as much as you want to practice their language too. And if all else fails, I suggest everyone polish their mime or drawing skills, because it sure helps when no one speaks the same language!

Picture 3:Immerse yourself in cultural activities and learn the language. A little karaoke never hurt anyone.