Reflections on my 8 years working with small-holder dairy farmers of Pakistan: a life changing experience; Part 1

Part 1: The complexities of buffalo production influenced who the project engaged with

The beginning: It was with some trepidation that I accepted the invitation issued by Peter Doyle, Chief Dairy Officer with the Victorian Department of Agriculture, to join a scoping mission to Pakistan to explore options for a project to assist Pakistan’s 8 million small-holder dairy farmers. The project emanated from discussions between our then Prime minister, John Howard, and Pakistan President of the time, Musharraf. The party included experts in dairy production, agronomy, nutrition, trade, economics and education. With the attention to detail in providing water-tight protection, it was clear that security was always going to be a challenge.

The machinations of some of the experts and politicians we met were hard to believe: millions of litres of milk to be harvested in Eastern Sindhi desert exuded from the vivid imagination of one Sindhi politician! Really?

Where to start? The very breadth of our project daunted us. One of our objectives was to:

Enhance the research capacity of Pakistani scientists in priority fields relevant to the ongoing development of the dairy sector.

You might think that the obvious candidate priority areas to improve productivity and on farm profits would be to improve knowledge of cattle/buffalo nutrition and maintaining healthy animals. How wrong this judgement proved to be. The further we immersed ourselves into the project the more we realised there were many more important limitations to the success of our project. I take the opportunity to highlight the most important of these below, in the hope that our experience helps others to look “outside the square”.

The unique nature of Pakistan’s buffalo: It is important to recognise the importance of the river buffalo to the Pakistani peoples. The greater fat content of buffalo milk (6.5%) is highly sought after by the consumer across the country, and so attracts a higher financial return to the producer. However, there are other socioeconomic reasons for farmers to keep buffalo.

Small-holder farmers keep buffalo as their “bank”, which they use as a source of finance for important family events like marriages, funerals and to meet family medical expenses. Their ownership is also a social status symbol within their village: thus ownership of 6 poorly fed buffalo may be a higher priority than owning 4 well fed animals. So how do we accommodate these social norms in our extension program when clearly 4 well fed animals provides a better financial outcome for the family?

Problems with buffalo reproduction: Buffalo come with limitations, chief of which is the difficulties encountered in obtaining successful pregnancies. Buffaloes exhibit late sexual maturity, long postpartum anoestrus, poor expression of oestrus, poor conception rates and long calving intervals. In many environments they breed year-round, although summer infertility is a major problem as it is with many species. We thought that under-nutrition was the major issue, until we discovered that many of the concentrate feeds purchased by small-holder farmers contain heroic concentrations of mycotoxins from fungus. These toxins disrupt ovarian function and pass directly from feed into milk and into the human food chain. This provides yet another example of where the livestock, agriculture and human health agencies need to work together to resolve a burning issue for dairy producers and consumers alike.

Figure 1. Fungus contaminated corn is a common sight where feed storage facilities are inadequate: this can lead to reproductive disorders in cattle and buffaloes

Understanding the marketing of the product: It is not just as simple as providing extension material on how to feed animals better. Imagine our surprise when we carefully analysed some of our survey data on the profitability of small-holder dairy operations to find that even the best farmers owning 6 or less animals were losing money on every litre they produced. In this case, how can you put a price or value on the importance of “social status”?

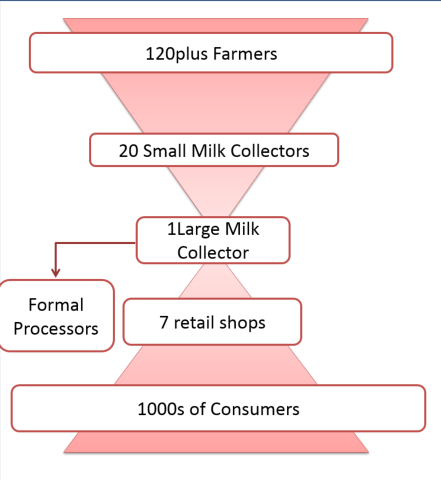

In investigating the factors influencing prices paid to farmers, we analysed the structure of traditional marketing chains along which 95% of small holder milk production flows. A typical structure is included in Figure 2. Our postgraduate students took their life in their own hands when attempting to obtain detail on trading activities along the chain.

Figure 2. The structure of a traditional milk marketing chain servicing the needs of small-holder dairy farmers. Red arrow = flow of milk, black arrows = loans.

The flow of milk follows the red arrow from the farmer to the consumer through at least 2 levels of milk collectors. The key large collector provides loans to the retailer to pay the rent for his shop location, and to the small collectors to then provide loans to farmers to purchase feed for their livestock. The formal processors obtain small quantities of milk to top up their own suppliers if they are short.

So what is wrong with these chains? Quite simply, the small and large collectors, as well as the retailers, dilute the milk to provide a profit margin for themselves and then adulterate the product to enhance its appearance for the poor unsuspecting consumer.

You then need to think about why this system ever came into being. Clearly the road infrastructure for milk transport is so poor that the only practical means of milk collection is through use of a motorbike or donkey cart. This presented an entrepreneurial opportunity for owners of bikes and small trucks which many have adopted to support their families. However, in essence the profits to be made through milk production and marketing in this system are largely retained by the milk collectors and retailers, with the poor farmer being recompensed insufficiently to pay for the cost of production.

Figure 3. Small volume milk collector measuring the milk that the farmer will be paid for

Is it little wonder that many farmers are not interested in advice to increase animal productivity? How do you engage milk collectors in extension activities to improve milk quality when they know that any practices that they adopt will threaten the profitability of their enterprise?

Quite clearly the development of effective extension services in this production and marketing system is fraught with challenges that extend to the very core of the social structure of village communities. The effective extension worker clearly needs skills in both technology as well as sociology.

The need to engage with the whole family and local government services: The time honoured practice of providing extension services to the male heads of families has yielded positive responses across the world. This practice has not accounted for the major contributions that the women and children of the family in running the family farm enterprise. It did not take us long to recognise that much of the entrepreneurial activity with small-holder farms is instigated and driven by women with assistance from their children. Our adoption success rates more than doubled once the same extension messages were delivered at the same time to meetings of women and men, with time for them to discuss their new-found information over the family meal.

Figure 4. Extension worker Zahra Batool demonstrating how to value add through ice cream manufacture

However, this is not the whole story. Village communities are provided with services by a range of government instrumentalities. These include those regulating agriculture, education, water resources, energy, public health and livestock veterinary services. Government departments globally most often exist in isolation, seldom communicating with each other, and Pakistan is no exception to this rule. In our program we have engaged with the livestock department in most of our activities, and yet all of these departments contribute to the prosperity of a community. So inviting the school teacher, for example, provided a pathway for extension material developed for children to be introduced to the classroom.

However, it is the village health worker who holds a key to success with any livestock extension activity. In some villages in rural Sindh, mothers had no understanding of the importance of colostrum to the wellbeing of their own newborn babies. In fact, they voided their first milk as the perception was that this milk made their offspring sick. Is it little wonder that these mothers then failed to provide the first milk or colostrum for their calves, but instead made it into sweets to provide as a gift for their neighbours and friends? Thus in this community, neither children nor calves thrived. A little co-operation between the village health and veterinary extension teams could have achieved so much.

Figure 5. Calf reared without access to colostrum and fed green forage, which their rumen is not sufficiently developed to digest

Tune in next week for Part 2 which looks at some of the broader issues of this type of work.