Communicating in Luang Prabang

by Tereza Nemanic

Tereza is a 4th year Bachelor of Animal Veterinary Bioscience student at The University of Sydney. As part of her final year honours project, she visited Luang Prabang to participate in the ACIAR funded project ‘Enhancing transboundary livestock disease risk management for poverty reduction in Lao PDR (AH/2012/067)’. Tereza is a recipient of an AsiaBound Mobility Scholarship, which supported her travel costs. The project is being implemented by The University of Sydney and the Department of Livestock and Fisheries, Lao PDR.

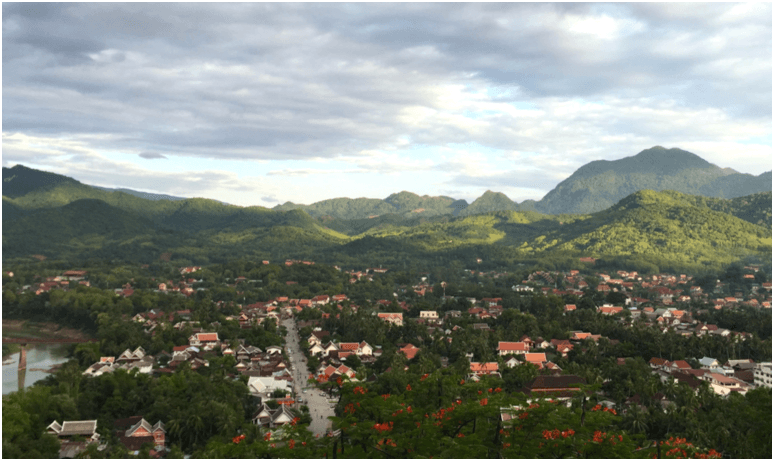

From my long 21 years of life, I’ve found that it’s not often that you’ll find yourself presented with an opportunity packed full with interests from so many corners of your life. That’s why when I heard about a chance to research health and disease in Southeast Asia I knew I had to get on board. I’ve just returned home to Sydney after spending one of the most calming yet hectic months of my life in Luang Prabang, a UNESCO World Heritage listed town in northern Laos. My project is a pilot study that will evaluate the use of medicated urea molasses blocks (MUMB) in smallholder village systems. The study is a response to the challenges of internal parasites and malnutrition of large ruminants, key constraints to improving the productivity of the livestock in Laos.

Within a few days of arriving in Luang Prabang, we had met and discussed the project with an endless number of staff from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, animal health workers, farmers and other stakeholders. A lesson that I learnt after a few awkward handshake lingers was that I was not to shake hands with men when introducing myself, and instead greet with a nod. This became a common story for the district staff when meeting farmers throughout the trip. Although I couldn’t understand the story due to my extremely poor (and basically non-existent) Lao, I now can confidently say that I’m extremely skilled at charades.

The project was carried out over four villages within Luang Prabang with two control villages and the other two being exposed to different treatments (medicated and non-medicated blocks). With the help of district staff and farmers we collected faecal samples from buffalo and cattle over five days before heading to the labs for analysis. Initially the faecal samples took longer to collect where we would spend the whole day collecting 20 samples (inclusive of the compulsory 2 hour nap after lunch). This was partially due to additional time for organising the logistics of the project, but mainly due to the lack of some key equipment. Faecal samples from the buffalo and cattle on the first two days were collected using regular food gloves and no lubricant. I knew that something needed to change when I began fearing collections, but it was made even clearer when I tried to return a wave to some of the children at the village but couldn’t lift my arm. By the third day we managed to buy some latex gloves and vegetable oil, both worked like a charm.

I was lucky enough to be invited to eat meals with the village headmen and staff during field collections and during my time at the lab. A huge part of my experience when I travel is made up by the food and the delicacies I have the opportunity to try. Even though the ingredients may be similar within dishes across different countries or even within different regions of a country, the flavours are always different. Also I am definitely the type of person who plans my dinner while I eat breakfast, so food definitely plays a huge part of my experience. I had the chance to eat amazing local Lao dishes everyday, something I realised is not actually that easy to find on the main road of Luang Prabang. I also ate some strange dishes such as bee larvae, snake soup and what I think was pig blood curd. We sometimes prepared the meals with the villagers, so I was also able to learn how to make a papaya salad (this is huge for someone whose specialty is toast).

Having meals with farmers and staff was not only amazing because of the food, but it also gave me an opportunity to communicate with them over something that was not language. The team and farmers I worked alongside spoke minimal English, and my Lao vocabulary was even less than that. My extensive Lao vocabulary was made up of 15 words when I returned to Sydney and included ‘hello’ and ‘thank you’, with the rest being comments about food. Meals gave me a chance to bond with the team I was working alongside, and I found that a food, a smile and some laughter can go a long way when words aren’t really an option. I also found that the stranger the dish you ate, the bigger the smile you received, and that the farmers really know how to drink their Lao-Lao (rice whisky).

The language barrier was easily the hardest challenge I experienced during the trip. It’s forced me to find alternative ways of communication and reminded me how far you can actually get if you stay optimistic, laugh and wear your eating pants. But it’s mainly highlighted how important verbal communication is, especially when working within a team. This project has allowed me the chance to not only work within a team alongside staff in the villages and laboratories, but within a completely new environment. I’ve definitely been thrown outside my comfort zone but it’s been great to know that what I thought was my limit isn’t actually that.